George Bernard Shaw famously said that “England and America are two countries divided by a common language,” and any American who’s ever been asked to write in British English has quickly seen why. The differences in American English vs. British English are many, and while there are a few rules of thumb you can follow when trying to adapt to British spelling, punctuation, and grammar rules, both dialects contain plenty of exceptions, contradictions, and things that just plain don’t make sense.

The differences between American and British English started with the Norman Conquest in 1066, when French started creeping into English, bringing not only new words but new spellings of words we already had. In the following centuries, some of those spellings shifted back to the original British ones, but in the 1700s, the English aristocracy became enamored with the fashionable French, adopting French-influenced spellings once again.

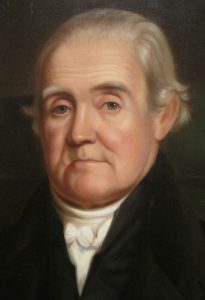

Then, after the American Revolution, British and American English diverged thanks largely to Noah Webster, who aimed to standardize and simplify spellings, an effort that culminated with the American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828. Webster believed in using spellings that more closely matched how we say words, and the result was that in many cases, he stripped out some of the French influences. Webster’s changes were largely adopted across America, and a few of them were incorporated into British spelling, too. But in many cases, the Brits responded by digging in their linguistic heels and insisting that their spellings were the correct ones, and so we have the many variances in British English vs. American English that remain today.

Then, after the American Revolution, British and American English diverged thanks largely to Noah Webster, who aimed to standardize and simplify spellings, an effort that culminated with the American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828. Webster believed in using spellings that more closely matched how we say words, and the result was that in many cases, he stripped out some of the French influences. Webster’s changes were largely adopted across America, and a few of them were incorporated into British spelling, too. But in many cases, the Brits responded by digging in their linguistic heels and insisting that their spellings were the correct ones, and so we have the many variances in British English vs. American English that remain today.

Here, then, for American writers who find themselves asked to write in British, are some of the major differences between British and American English.

Guidelines for British Spellings

-or/-our

Many common words that end in -or end in -our across the pond, so we disagree with the British on how to spell “favorite,” “color,” and “neighbor.” They say “favourite,” “colour,” and “neighbour.”

-ize/-ise, -yze/-yse

What do the Brits have against Z (or “zed,” as they call it)? You might start to wonder when you see words like “civilise.” If it ends in -ize or -yze here, it probably ends in -ise or -yse there, so whether it’s “realise” or “realize,” “analyse” or “analyze” depends on what country you’re in.

-er/-re

How do you spell “theater”? If you’re in New York, you might enjoy a night out at a Broadway theater, but if you’re going to the West End for a show, you’re headed to the “theatre.” Similarly, you’ll see “centre” for “center” and “metre” for “meter.”

-og/-ogue

If a word ends in -og here, it likely ends in -ogue there. The most common example of this British English spelling convention is “catalogue.”

-ce/-se

For a noun ending in -ce, the verb form will generally end in -se: They say “practice” as a noun but “practise” as a verb, for instance. American English usually picks one form and sticks with it, such as “license” and “practice,” which are both nouns and verbs here.

Adding -s or -st

The British spellings of some prepositions add an extra -s or -st, such as in “towards” or “amongst.”

Retained ligatures

As English lost the ligatures æ and œ, the British converted them to digraphs, such as in “orthopaedic,” “encyclopaedia,” and “manoeuvre.” Meanwhile, Webster stripped them down to single vowels, so we save a little ink when we spell “orthopedic,” “encyclopedia,” and “maneuver.”

Doubled consonants

Verbs ending in a vowel followed by L often double the L when you add a suffix that starts with a vowel, such as in “traveller” or “cancelling” instead of the American “traveler” and “canceling.” But this is a pretty tricky area because the British aren’t consistent about it, and neither are we: We use “excelling,” for example, but they use “fooling.”

Other oddities of British English spelling

Here are a few other differences in British vs. American spelling that don’t seem to fall under any specific rule of thumb but might be helpful to know:

| American | British |

| airplane | aeroplane |

| aluminum | aluminium |

| artifact | artefact |

| check | cheque |

| cozy | cosy |

| gray | grey |

| inquire | enquire |

| Mom | Mum |

| pajamas | pyjamas |

British Punctuation and Grammar

No Oxford commas

You might think that the country where Oxford commas came from would use them, but no. The truth is that the only place in Britain that uses the serial comma is, well, the Oxford University Press. While a lot of Americans like it, they’ll find very little company: The Brits don’t use it, the Canadians don’t use it, and neither do the world’s English-speaking journalists.

Single-quotes first

While we use double quotation marks (“”) to enclose a quote, in Britain, they prefer single ones instead (‘’).

Punctuation after quotes

In the U.S., if we’re writing a sentence that’s a quote, we’ll usually put the period or comma at the end before the closing quotation mark. But in the U.K., they usually close the quotation marks first, then write the period or comma.

Dropped periods after titles

If an abbreviation of an English courtesy title includes the first and last letters of a word, it doesn’t need a period after it in British English, so they’d write “Mr John Smith” or “Dr Mary Jones” without punctuation.

Pluralizing collective nouns

In America, we often treat a company, brand, or other group as a singular collective noun taking a singular verb. But the British often treat these as plurals, taking plural forms of verbs, so they might say things like “IBM issued their earnings report” or “the team have won three games in a row.”

More use of “got”

The British seem to like the word “got” a whole lot. For one, they don’t use the word “gotten”: While we’d say that “it’s gotten windy out there,” they’d just say that “it’s got windy out there.” Also, where we use “have,” the Brits tend to use “have got.” While we say “they have three apples,” they’d say “they’ve got three apples,” and if I want to say that “I have to go home early” and I’m writing for a British audience, I’d say that “I’ve got to go home early.”

“In hospital”

Here’s one specific quirk that has come up a lot in past projects: In British English, if you’re in the hospital, you’re merely “in hospital.” They draw a very fine distinction between being “in hospital,” meaning that you’re a patient being treated there, and being “in the hospital,” which to them often means only that you’re physically inside of a hospital building. It can also mean that someone is a patient at a specific hospital that’s already been referred to by name.